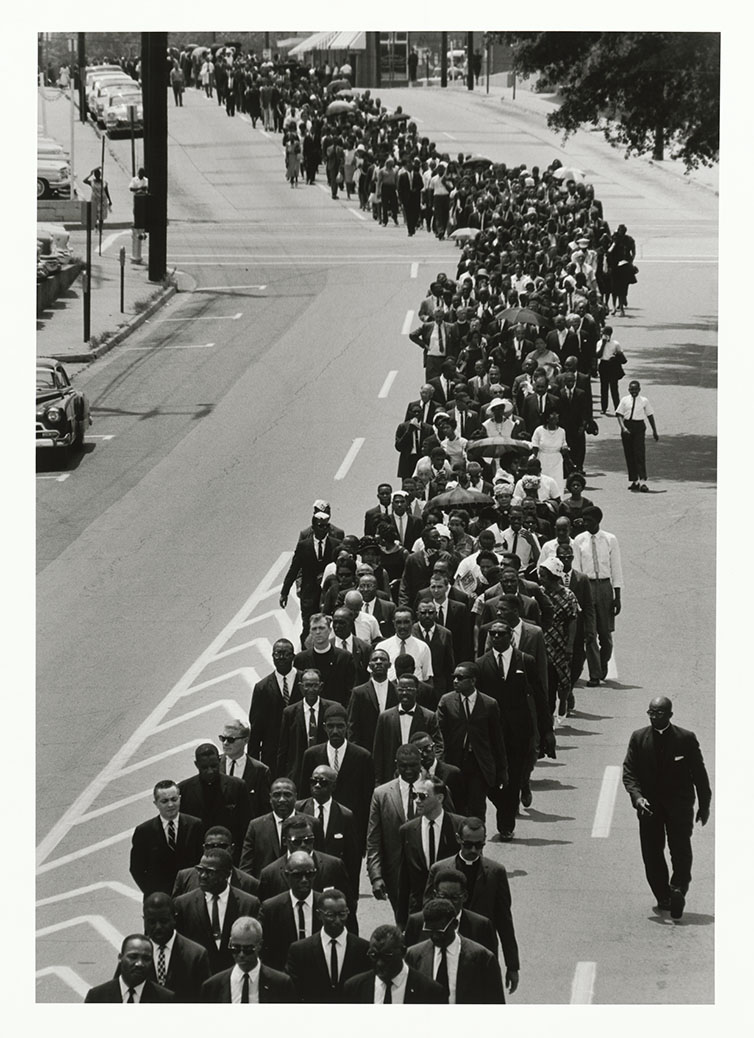

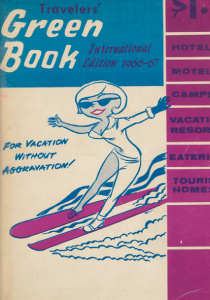

The Green Book listed some of the most significant locations central to the movement.

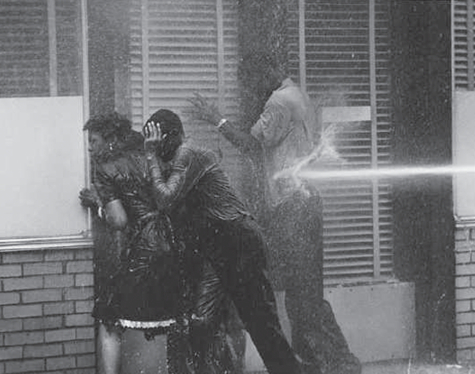

Without safe places to plan, strategize, debrief, and recuperate, civil rights leaders of the 1950s and 60s would have failed to push social justice forward in America. From hotels to beauty shops, these places became the headquarters for holding America accountable to its promise of liberty and justice for all.