By the 1930s, there were nearly thirty million cars on the road, and 85% of Americans vacationed by car. Significantly, the car industry created a new path to prosperity for Black Americans. In a Jim Crow world, where policy limited access to affordable housing and neighborhoods of choice, having a car opened your world. It was a prized possession, as thrilling as it was useful. It was a portal to humanity, from work and family functions to household needs and leisurely getaways.

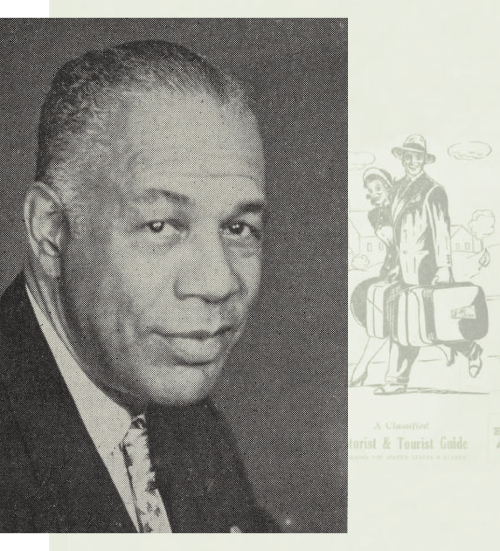

Credit: The Travelers' Green Book, 1960. Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, Manuscripts, Archives, and Rare Books Division, The New York Public Library.

Credit: The Negro Motorist Green Book, 1947. Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, Manuscripts, Archives, and Rare Books Division, The New York Public Library.

“The automobile has been a special blessing to the Negro.”—The Negro Motorist Green Book, 1938 edition

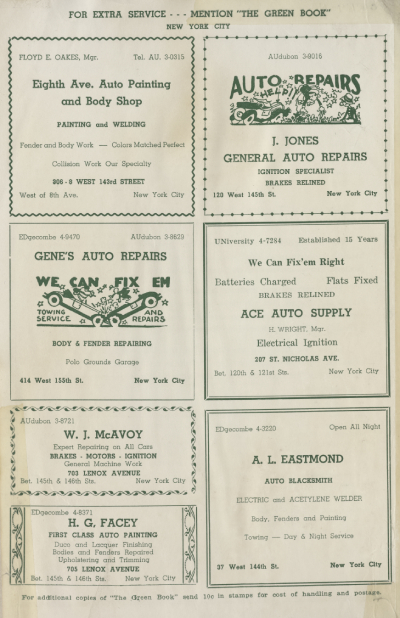

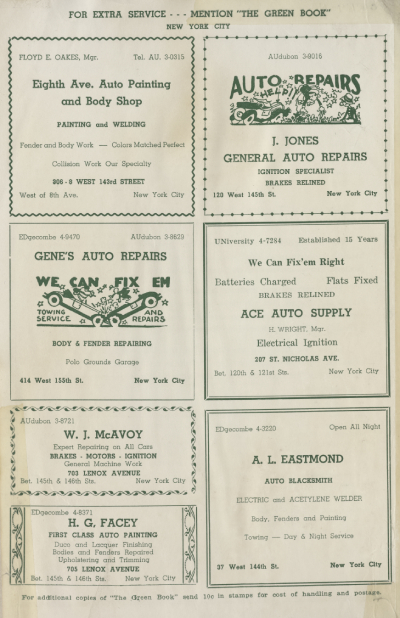

Credit: The Negro Motorist Green Book, 1937. Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, Manuscripts, Archives, and Rare Books Division, The New York Public Library.

Mechanics could earn as much as $25 to $50 a week. Many Black men migrated to northern cities to earn these higher wages, ensuring a better standard of living—enabling many the opportunity to buy a car of their own.

Credit: [Auto mechanic Sam "Scotty" Scott], ca. 1944. Charles "Teenie" Harris. Collection of the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture, Gift from Charles A. Harris and Beatrice Harris in memory of Charles "Teenie" Harris, (C) Carnegie Museum of Art, Charles "Teenie" Harris Archive.

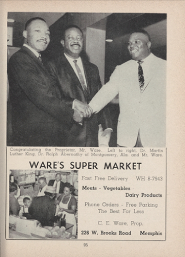

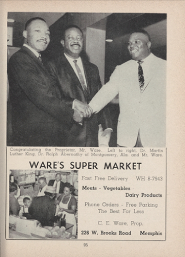

Since legal enslavement, financial independence has been critical to Black liberation in America. The Green Book would not have been possible if not for the community of self-sufficient, talented, and successful Black businesses that filled its pages. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., on the left, understood the significance of Black businesses to Black civil rights.

Credit: The Travelers' Green Book, 1960. Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, Manuscripts, Archives, and Rare Books Division, The New York Public Library.

Click on the images to learn more information