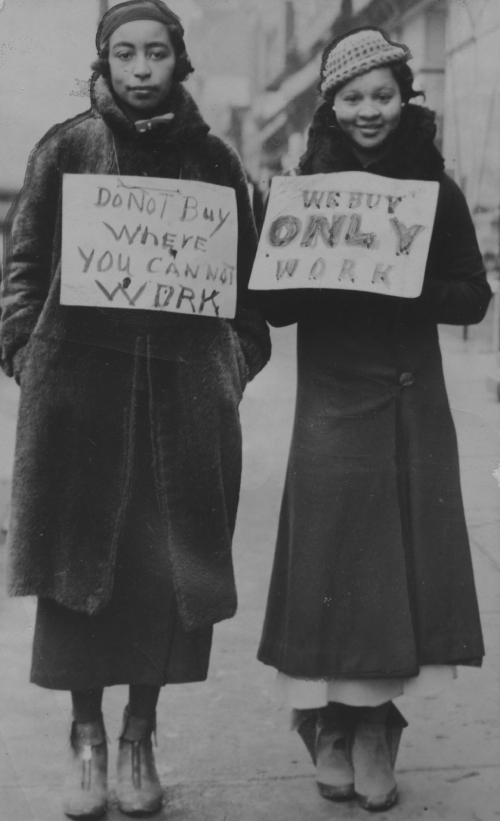

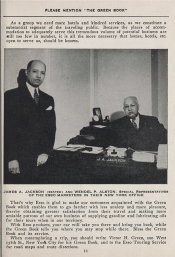

Harlem Women Protesting

In the early 1930s, Black Americans banded together to create the “Don’t Buy Where You Can’t Work” campaign. The campaign galvanized Black communities to boycott businesses that wouldn’t hire them. The Negro Motorist Green Book was born in the midst of the 1935 race riot in Harlem and a decade after the “Don’t Buy Where You Can’t Work” campaign.

[If you can't shop there, don't work there], 1940. [Afro American Newspapers/Gado/Contributor]/[ArchivePhotos] via Getty Images.

Small's Paradise

Founded in 1925, at the height of the Harlem Renaissance, Smalls Paradise was listed in the Green Book between 1938 and 1967. Edwin Alexander Smalls ran it for more than thirty years, and in the 1920s it was one of the few integrated nightclubs owned by a Black man.

In the early 1940s, Victor Green moved his operation out of his home and into an office above Smalls Paradise.

Credit: Exterior of Smalls Paradise, Harlem, 1955. Photograph by Austin Hansen used by permission of the Estate of Austin Hansen, and may not be copied. Photographs and Prints Division, Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, The New York Public Library.

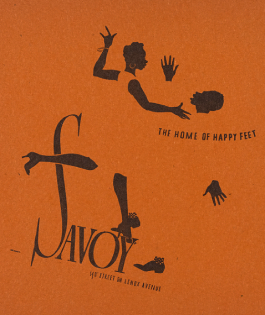

The Savoy

One of the most famous nightclubs in Harlem was another Green Book site, The Savoy. Opened in 1926, The Savoy was the size of an entire city block, and was one of the first integrated clubs in Harlem. Two bandstands hosted the best performers at the height of their careers, including Benny Goodman, Thelonious Monk, and Charlie Parker.

[Souvenir Card for Savoy], 1926-1958. Manuscripts, Archives and Rare Books Division, Schomburg Center for Reseach in Black Culture, The New York Public Library.

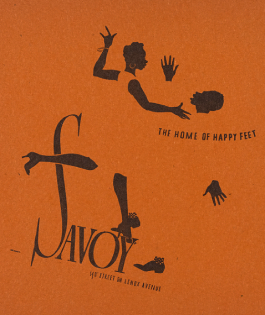

Plays of Negro Life

During the Harlem Renaissance, there was an explosion of Black intellectualism and artistic expression, producing greats like Zora Neale Hurston, W.E.B Du Bois, Alain Locke, Augusta Savage, and Langston Hughes.

The modernist cover created by the artist Aaron Douglas gives creative cadence to this movement of African American affirmation.

Credit: Plays of Negro Life: A Source-Book of Native American Drama, 1927. Ed. Alain LeRoy Locke and Thomas Montgomery Gregory. Collection of the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture, © Aaron Douglas Foundation/Licensed by Visual Artists & Galleries Association, Inc. (VAGA), New York, NY.

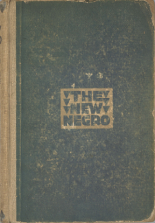

The New Negro

…the present generation will have added the motives of self-expression and spiritual development to the old and still unfinished task of making material headway and progress. No one who … views the new scene with it still abundant promise can be entirely without hope. …if in our lifetime the Negro should not be able to celebrate his full American democracy…he can at least…celebrate the attainment … of a spiritual Coming of Age.

The New Negro: An Interpretation, 1925. Ed. Alain LeRoy Locke. Collection of the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture © 1925 by Albert and Charles Boni, Inc.

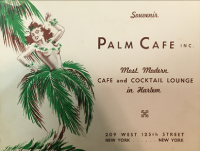

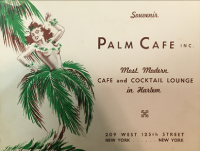

Palm Café

Palm Café Inc. souvenir photo card, 1959

Credit: [Souvenir Card for Palm Cafe]. Collection of Arthur L. Field.

Click on the images to learn more