Jack’s Basket Room (also known as Jack’s Chicken Basket) was a popular Green Booki> site opened in the heart of South-Central Los Angeles in 1939. Owned by Jack Johnson, the first Black heavyweight boxing champion, the Basket Room hosted the nation’s top entertainers and served the Black upper class.

Performers at Jack's Basket Room, Los Angeles, 1949. Charles White. Courtesy of the Tom & Ethel Bradley Center at California State University, Northridge.

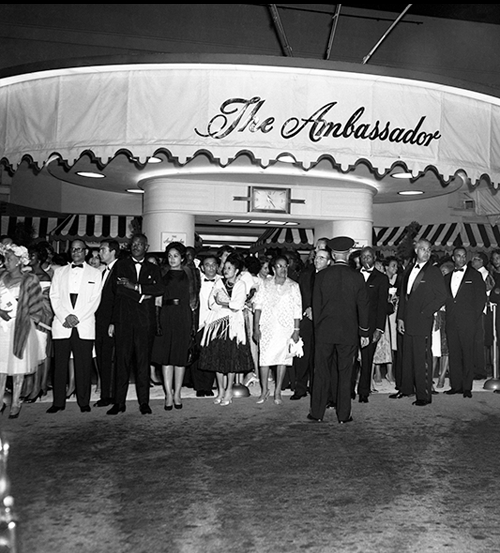

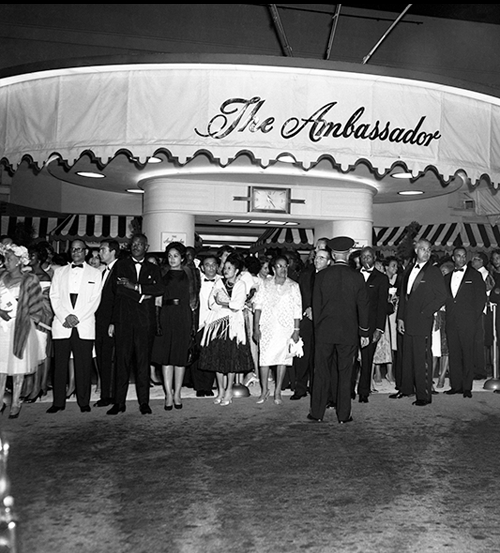

The Ambassador Hotel was one of Los Angeles’ premier destinations, and a popular Green Book destination. The Ambassador was listed in the guide in the 1963–64 and1966–67 editions.

Nat King Cole Anniversary, Los Angeles, 1962. Harry Adams. Provided by the Harry Adams Photograph Family Archive. Courtesy of the Tom & Ethel Bradley Center at California State University, Northridge.

[Audrey Lee and nephew on sidewalk], ca. 1941. [Shades of L.A. Photo Collection]/Los Angeles Public Library.

Hat Shop, Los Angeles, 1964. Harry Adams. Provided by the Harry Adams Photograph Family Archive. Courtesy of the Tom & Ethel Bradley Center at California State University, Northridge.

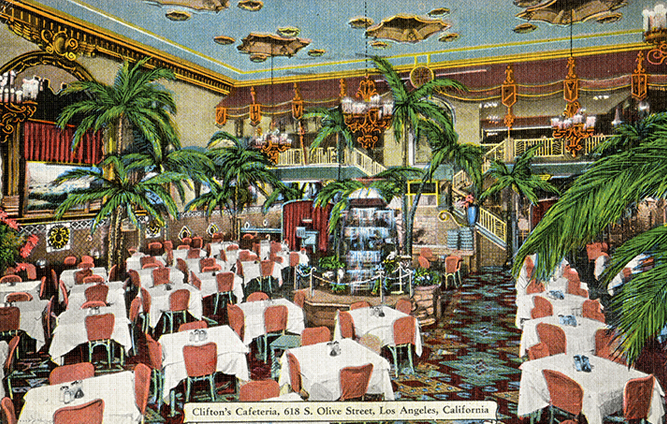

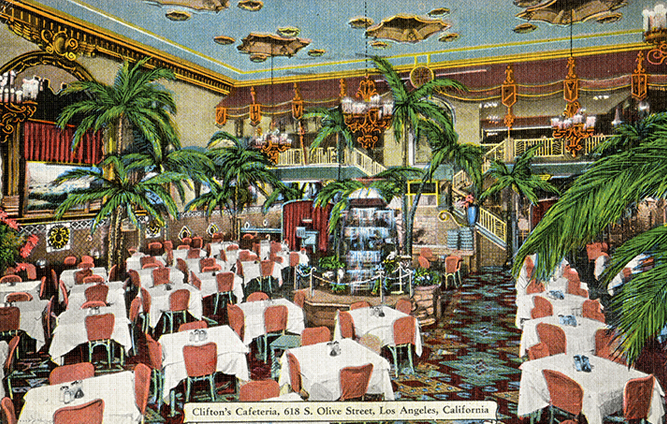

Another western destination listed in the Green Book was Clifton’s Cafeteria, a restaurant on Broadway in downtown Los Angeles. It was a sprawling five-story establishment located at the end of Route 66.

[Clifton's Cafeteria postcard], ca. 1939. [Security Pacific National Bank Photo Collection]/Los Angeles Public Library.

Click on the images to learn more information